PRAGUE, Czech Republic, April 27 (UPI) –– Flames began to engulf the young man at the foot of Riga’s Freedom Monument. A brilliant 21-year-old student at the University of Latvia, Ilya Rips could not sit idly by. Still in flames, Rips held a sign, “I am protesting the occupation of Czechoslovakia.” It was 40 years ago — on April 13, 1969 — three months after Jan Palach had immolated himself to protest the Soviet invasion in Prague.

I did not know who Rips was. He was saved by passersby. He has come to appreciate this.

I met this soft-spoken and reserved hero, now an Israeli citizen and professor at the prestigious Holon Institute of Technology, last week at the Latvian Embassy. Ambassador Argita Daudze had invited a small group of academics, former dissidents and political types to a “glass of wine” in honor of Rips.

Edgars Bondars, the Latvian counselor — whose mother-in-law had been sent to Siberia at age 2, and I were standing with Eduard Outrata and his wife Jana. The retired Czech senator and Czech-Canadian emigre had left Czechoslovakia in 1968 and come back after the fall of communism. A man in the garb of an Orthodox Israeli walked in behind the ambassador. I had expected many things, but not this. Rips was introduced, and a murmur trickled through the room.

Ilya Rips was considered a mathematical genius when he entered the University of Latvia at 15. He had never practiced Judaism. Three of his four grandparents had been killed in the Shoah — the Holocaust. “I wasn’t exposed to Judaism until I immigrated to Israel in 1972,” Rips said to me when I interviewed him later.

The Russians identified their Jewish citizens as a national ethnic group. “Jivre” was stamped in the passport of every Jewish Soviet citizen. Most were secular — and that might have already been too much religion for them. During the ’70s, the Russian authorities began to let Jewish dissidents, “refuseniks,” immigrate to Israel.

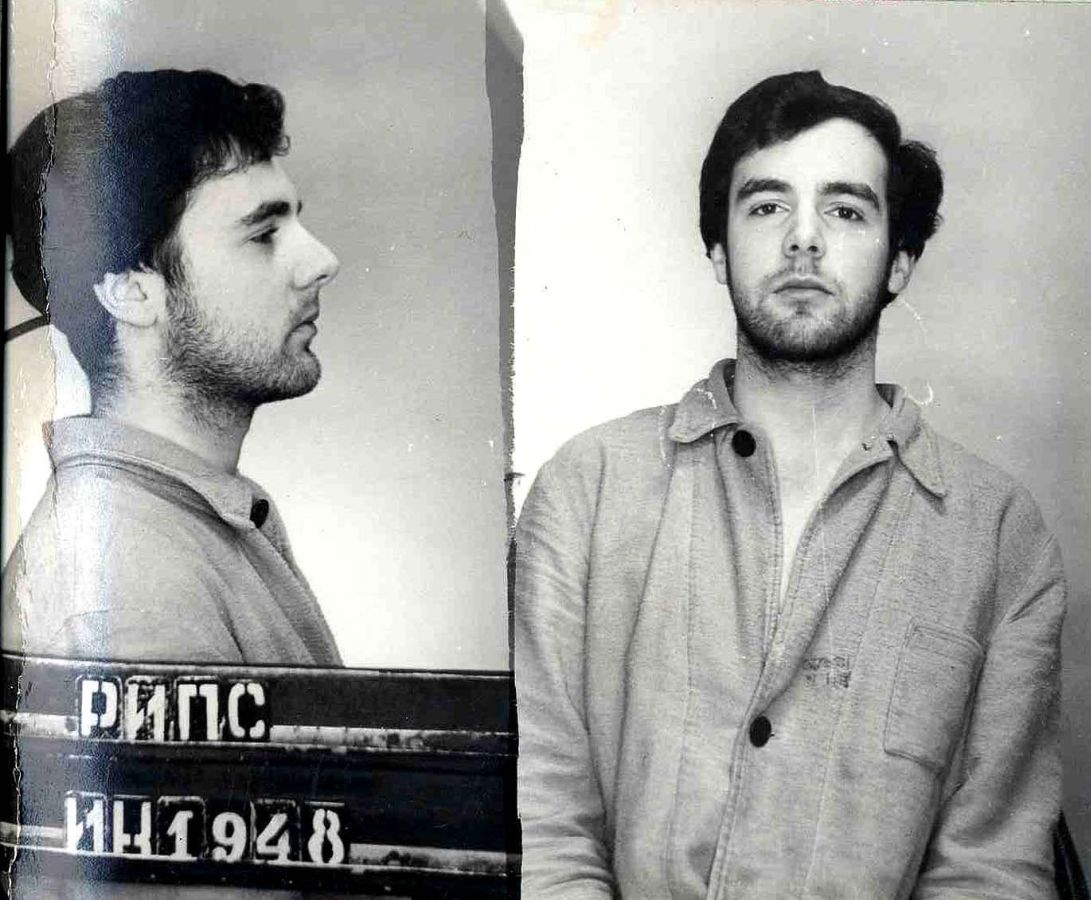

Rips, who now bears the Hebrew name Elijahu, would emigrate with the second wave of refuseniks in 1971, after harrowing years of a show trial, interrogations, contrived mental examinations and forced internment in a psychiatric hospital. “The Soviet authorities and KGB used psychiatric terror as a way to muzzle dissent. If you could prove someone was insane, then their points of view were irrelevant. Forced psychiatric internment had the added benefit that the ‘cure’ was not restricted by time. Dissidents could be interned indefinitely.”

“I was lucky,” Rips said with a wry grin — maybe even a grimace, “that I was interned in a regular psychiatric hospital in Riga. The special ones deep in Russia were particularly despicable — with injections, drugs and torture. Of course I was given pills, but I did not swallow them.” The Latvians helped him. “They had the best attitude. Even my parents and other people were permitted to visit me.” Rips said this matter-of-factly, as though it had been any normal hospital. It certainly was not.

During the interview with Rips, noted anti-communist fighter Barbara Day was present. She had been to a trial just a little earlier in Prague of a former member of the StB, the Communist Secret Police in Czechoslovakia. This interrogator had bullied a friend of hers until he was driven into exile. There are not nearly enough prosecutions of these despicable individuals.

The former head of the Communist Secret Police in Czechoslovakia, Major-General Alojz Lorenc — a senior adviser to the corrupt Penta Group, the sons of former apparatchiks — is living fast, free and easy in Slovakia. He is entertained by Western business groups as though nothing ever happened. It is revolting.

Only recently has the Czech government — and it has not always been so — given the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes in Prague enough power and money to be effective. For years, its forerunner was kept alive but badly funded as an alibi. Professor Rips was a guest of the institute. He met with students commemorating the 20 years since the fall of communism.

I had been given access to the institute’s vast files a year ago. Miroslav Lehky, a hero of the underground movement and now deputy director, had shown me around. I had checked the files of some individuals to see if they were corrupted by the Communist Secret Police. They were. A group of young dedicated staff are sifting through the miles of former secret files to catalog them and put them into a modern data bank. They discovered Rips’s story.

“I was alone. People around me had similar feelings,” Rips said of his reason for immolating himself. “I had no political objectives. My mentor, Professor Boris Plotkin, had no idea about my intentions. He was later forced out of his position by the KGB for having been ‘unsuccessful in educating me about life.’ I even wrote mathematical papers while they were trying to prove I was insane — to show I was not. God, how naive.”

Rips gives much of the credit for his release to Professor Littman Bers, whose father lived in Riga. Bers and an organization of U.S. mathematicians pressed the Soviets on Rips’s behalf. The Soviets hated bad press. They were sensitive to pressure. After six months of prison and 1.5 years in a mental hospital, Rips was freed. This was extremely weak by Soviet standards.

“It was truly evil, and people must be kept aware of it,” said Jana Outrata, the retired senator’s wife, whose own family was disenfranchised during communism.

Many silent heroes of the time remain anonymous to this very day.

—

(UPI International Columnist Marc S. Ellenbogen is chairman of the Berlin, Copenhagen and Sydney-based Global Panel Foundation and president of the Prague Society. A founding trustee of the Democratic Expat Leadership Council and a member of the National Advisory Board of the U.S. Democratic Party, he has advised many political candidates.)